"Writing Advice: by Chuck Palahniuk

In six seconds, you’ll hate me.

But in six months, you’ll be a better writer.

But in six months, you’ll be a better writer.

From this point forward—at least for the next half year—you

may not use “thought” verbs. These include: Thinks, Knows, Understands,

Realizes, Believes, Wants, Remembers, Imagines, Desires, and a hundred others

you love to use.

The list should also include: Loves and Hates.

And it should include: Is and Has, but we’ll get to those later.

And it should include: Is and Has, but we’ll get to those later.

Until some time around Christmas, you can’t write: Kenny

wondered if Monica didn’t like him going out at night…”

Instead, you’ll have to Un-pack that to something like: “The

mornings after Kenny had stayed out, beyond the last bus, until he’d had to bum a ride or pay for a cab and got home to find Monica faking sleep, faking because she never slept that quiet, those mornings, she’d only put her own cup of coffee in the microwave. Never his.”

mornings after Kenny had stayed out, beyond the last bus, until he’d had to bum a ride or pay for a cab and got home to find Monica faking sleep, faking because she never slept that quiet, those mornings, she’d only put her own cup of coffee in the microwave. Never his.”

Instead of characters knowing anything, you must now present

the details that allow the reader to know them. Instead of a character wanting

something, you must now describe the thing so that the reader wants it.

Instead of saying: “Adam knew Gwen liked him.” You’ll have

to say: “Between classes, Gwen had always leaned on his locker when he’d go to

open it. She’s roll her eyes and shove off with one foot, leaving a black-heel

mark on the painted metal, but she also left the smell of her perfume. The

combination lock would still be warm from her butt. And the next break, Gwen

would be leaned there, again.”

In short, no more short-cuts. Only specific sensory detail:

action, smell, taste, sound, and feeling.

Typically, writers use these “thought” verbs at the

beginning of a paragraph (In this form, you can call them “Thesis Statements”

and I’ll rail against those, later). In a way, they state the intention of the

paragraph. And what follows, illustrates them.

For example:

“Brenda knew she’d never make the deadline. was backed up from the bridge, past the first eight or nine exits. Her cell phone battery was dead. At home, the dogs would need to go out, or there would be a mess to clean up. Plus, she’d promised to water the plants for her neighbor…”

“Brenda knew she’d never make the deadline. was backed up from the bridge, past the first eight or nine exits. Her cell phone battery was dead. At home, the dogs would need to go out, or there would be a mess to clean up. Plus, she’d promised to water the plants for her neighbor…”

Do you see how the opening “thesis statement” steals the

thunder of what follows? Don’t do it.

If nothing else, cut the opening sentence and place it after

all the others. Better yet, transplant it and change it to: Brenda would never

make the deadline.

Thinking is abstract. Knowing and believing are intangible.

Your story will always be stronger if you just show the physical actions and

details of your characters and allow your reader to do the thinking and

knowing. And loving and hating.

Don’t tell your reader: “Lisa hated Tom.”

Instead, make your case like a lawyer in court, detail by

detail.

Present each piece of evidence. For example: “During roll

call, in the breath after the teacher said Tom’s name, in that moment before he

could answer, right then, Lisa would whisper-shout ‘Butt Wipe,’ just as Tom was

saying, ‘Here’.”

One of the most-common mistakes that beginning writers make

is leaving their characters alone. Writing, you may be alone. Reading, your

audience may be alone. But your character should spend very, very little time

alone. Because a solitary character starts thinking or worrying or wondering.

For example: Waiting for the bus, Mark started to worry

about how long the trip would take…”

A better break-down might be: “The schedule said the bus

would come by at noon, but Mark’s watch said it was already 11:57. You could

see all the way down the road, as far as the Mall, and not see a bus. No doubt,

the driver was parked at the turn-around, the far end of the line, taking a

nap. The driver was kicked back, asleep, and Mark was going to be late. Or

worse, the driver was drinking, and he’d pull up drunk and charge Mark

seventy-five cents for death in a fiery traffic accident…”

A character alone must lapse into fantasy or memory, but

even then you can’t use “thought” verbs or any of their abstract relatives.

Oh, and you can just forget about using the verbs forget and

remember.

No more transitions such as: “Wanda remembered how Nelson

used to brush her hair.”

Instead: “Back in their sophomore year, Nelson used to brush

her hair with smooth, long strokes of his hand.”

Again, Un-pack. Don’t take short-cuts.

Better yet, get your character with another character, fast.

Get them together and get the action started. Let their actions and words show their thoughts. You—stay out of their heads.

Get them together and get the action started. Let their actions and words show their thoughts. You—stay out of their heads.

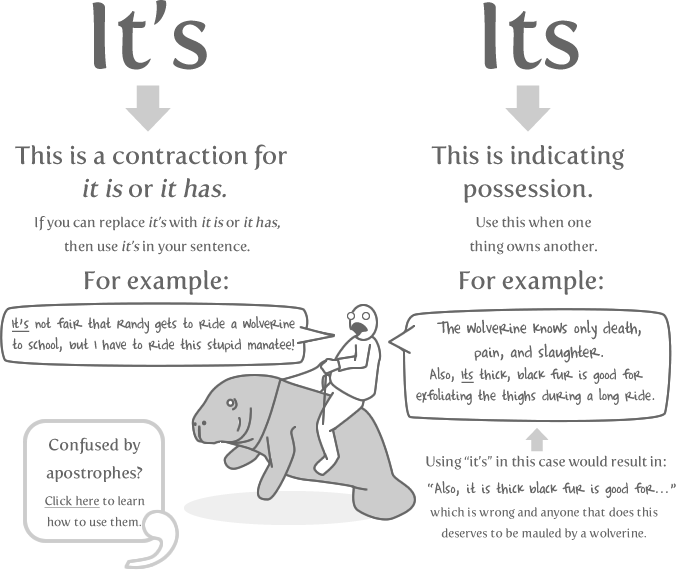

And while you’re avoiding “thought” verbs, be very wary

about using the bland verbs “is” and “have.”

For example:

“Ann’s eyes are blue.”

“Ann’s eyes are blue.”

“Ann has blue eyes.”

Versus:

“Ann coughed and waved one hand past her face, clearing the

cigarette smoke from her eyes, blue eyes, before she smiled…”

Instead of bland “is” and “has” statements, try burying your

details of what a character has or is, in actions or gestures. At its most

basic, this is showing your story instead of telling it.

And forever after, once you’ve learned to Un-pack your

characters, you’ll hate the lazy writer who settles for: “Jim sat beside the

telephone, wondering why Amanda didn’t call.”

Please. For now, hate me all you want, but don’t use thought

verbs. After Christmas, go crazy, but I’d bet money you won’t.

(…)

For this month’s homework, pick through your writing and

circle every “thought” verb. Then, find some way to eliminate it. Kill it by

Un-packing it.

Then, pick through some published fiction and do the same

thing. Be ruthless.

“Marty imagined fish, jumping in the moonlight…”

“Nancy recalled the way the wine tasted…”

“Larry knew he was a dead man…”

Find them. After that, find a way to re-write them. Make

them stronger.”